Executive Summary

The flour milling industry in Bangladesh stands at a critical juncture, embodying the nation’s broader economic narrative of rapid growth constrained by structural vulnerabilities. Once a peripheral commodity in a rice-centric food culture, wheat flour has ascended to become the country’s second most important staple, cementing the milling industry’s role as a cornerstone of national food security. This transformation is propelled by powerful secular trends: rapid urbanization, rising disposable incomes, and a fundamental shift in dietary habits toward convenience and processed foods. The market is characterized by robust and growing demand, with consumption expanding not only in households but also in burgeoning downstream sectors such as bakeries, institutional food service, and a nascent export market for value-added food products.

In response to this demand, the industry is undergoing a profound technological and structural evolution. A wave of significant capital investment by the nation’s largest conglomerates is replacing traditional, small-scale ‘chakki’ mills with state-of-the-art, automated roller mills, some of which are among the largest and most advanced in South Asia. This modernization is fostering greater efficiency, improving product quality, and enabling the introduction of innovative, value-added products that cater to an increasingly sophisticated consumer base. A competitive oligopoly has emerged, dominated by a few well-capitalized players who leverage brand equity, extensive distribution networks, and economies of scale to secure market leadership.

However, this dynamic domestic market is built upon a precarious foundation: an almost total dependence on imported wheat. With domestic production satisfying less than 15% of annual demand, the industry is acutely exposed to the volatility of global commodity markets, geopolitical disruptions, and macroeconomic pressures such as currency depreciation and dwindling foreign exchange reserves. The recent Russia-Ukraine conflict served as a stark reminder of this vulnerability, causing severe price shocks and supply chain uncertainty. Consequently, the industry’s profitability and stability are intrinsically linked to the government’s trade policies and its ability to navigate a complex geopolitical landscape, as evidenced by recent strategic import agreements designed to achieve diplomatic as well as economic objectives.

This report provides a comprehensive strategic analysis of the Bangladeshi flour milling industry, dissecting the interplay of these forces. It examines the drivers of consumption, the complexities of the global supply chain, the evolving industrial infrastructure, the competitive dynamics among key players, and the overarching regulatory framework. The analysis reveals an industry where the primary strategic imperatives are twofold: first, to master supply chain risk through diversified sourcing, strategic storage, and hedging; and second, to capture value in the domestic market through sustained investment in brand equity, product innovation, and operational efficiency. For investors, corporations, and policymakers, understanding this central tension between a thriving domestic market and a volatile global supply chain is the key to unlocking the future potential of this vital sector.

Section 1: The New Bangladeshi Diet: Market Dynamics and Consumption Drivers

1.1 From Field to Table: The Ascendance of Wheat as a Staple Food

While Bangladesh remains a predominantly rice-consuming nation, the last two decades have witnessed a profound and accelerating shift in its dietary landscape. Wheat has firmly established itself as the second most important food staple, transitioning from a supplementary grain to an integral component of the national diet.1 This ascendance is not merely a matter of caloric substitution but represents a fundamental change in food culture, making the flour milling industry a critical pillar of the country’s food security apparatus.1 Currently, wheat and its derivatives account for approximately 12% of total cereal consumption in the country, a figure that underscores its systemic importance.2

This trend is quantitatively substantiated by official consumption data. According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES), daily per capita wheat consumption saw a marked increase from 12.08 grams in 2005 to 19.83 grams in 2016.1 Further research from the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS) in 2012 indicated that the national average per capita consumption of wheat flour had reached 46 grams per day.2 This aggregate figure, however, conceals a significant urban-rural divide; consumption in urban centers was recorded at a substantial 83 grams per day, more than triple the rural figure of 25 grams per day.2 This disparity highlights that the dietary shift is being led by the country’s rapidly growing urban population, while also pointing to the immense latent potential for growth in rural markets as incomes and infrastructure improve.

1.2 Analyzing Demand: Urbanization, Income Growth, and Shifting Consumer Preferences

The surge in flour consumption is not a random phenomenon but is deeply rooted in the powerful socioeconomic transformations reshaping Bangladesh. The primary catalysts for this demand growth are a confluence of factors including rapid urbanization, a steady rise in disposable incomes, an increase in the number of women joining the formal workforce, and a growing health consciousness among the populace.1 These demographic and economic shifts collectively foster a consumer environment that values convenience, consistency, and the perceived health benefits of packaged and processed foods, for which flour is a fundamental ingredient.

The increasing popularity of fast-food chains and the adoption of more modern, time-constrained lifestyles, particularly in major urban hubs like Dhaka and Chittagong, have directly fueled the demand for flour and a wide array of wheat-based products.1 This evolution is transforming flour from a basic commodity, purchased loose from local mills, into a key component of a modernizing food culture that embraces everything from morning toast and packaged biscuits to evening noodles and restaurant-prepared meals. This process represents a classic maturation cycle seen in many developing FMCG markets. The transition from unbranded, loose flour to packaged, branded products is a clear indicator of a market moving up the value chain. It creates a new competitive arena where success is determined not just by the efficiency of milling operations but by the ability to build brand trust, communicate perceived quality (often judged by attributes like whiteness or fineness), and drive product innovation. Companies that recognize and capitalize on this shift are positioning themselves for long-term market leadership.

1.3 Downstream Growth: The Role of Bakeries, HRI, and Processed Food Industries

The vitality of the flour milling industry is inextricably linked to the robust growth of its downstream customers. The expansion of a sophisticated, and increasingly export-oriented, food processing sector that manufactures products like noodles, breads, biscuits, crackers, and various snacks is a primary consumer of milled flour.2 This industrial demand requires a consistent supply of high-quality, standardized flour, which only modern, large-scale roller mills can reliably provide.

Simultaneously, the hotel, restaurant, and institutional (HRI) sector has become a significant and discerning consumer of premium wheat flour, catering to both local and international clientele.3 A more recent but rapidly growing demand vector is the animal feed industry. Coarse wheat flour (atta) and wheat bran, a by-product of the milling process, are increasingly being incorporated into feed rations for the poultry, aquaculture, and cattle sectors. With the livestock and fisheries industries expanding to meet rising domestic protein demand, wheat consumption for feed is projected to continue its upward trend.7

1.4 Consumer Profile: Brand Loyalty, Purchase Drivers, and Retailer Influence

Understanding the end-consumer is crucial in this evolving market. A survey of over 100 consumers in Dhaka provided critical insights into purchasing habits and brand preferences. A key finding was a strong inclination towards bulk purchases, with most respondents buying flour as part of their monthly grocery shopping to secure price benefits. This is coupled with a high rate of consumption, as 57% of surveyed consumers reported using more than 2 kilograms of flour per week.3

Brand loyalty is emerging as a significant market force. The survey identified three primary factors influencing a consumer’s choice of brand:

- Perceived Quality (45%): This is the most important driver. Consumers often use heuristics such as the whiteness and fineness of the flour, or rely on advice from retailers, to judge quality.

- Availability (35%): The importance of a robust distribution network cannot be overstated. Consumers exhibit a high tendency to switch brands if their preferred product is out of stock.

- Promotion (11%): Marketing and promotional activities play a major role in building brand awareness and influencing purchase decisions at the point of sale.3

Interviews with retailers and dealers reinforce these findings from a supply-side perspective. For retailers, the commission offered by a company is the single most attractive incentive to actively promote a particular brand. This highlights the power of trade marketing in a low-involvement category like flour. The critical importance of distribution is further evidenced by the decline of formerly prominent brands like Yusuf and Noorani, which lost significant market share primarily due to weaknesses in their supply chains.3 This dynamic underscores that for any player in the Bangladeshi flour market, achieving success requires a dual focus: building a compelling brand promise for the consumer while ensuring that promise is consistently delivered through a flawless and far-reaching distribution network.

Table 1: Key Market Indicators for the Bangladesh Flour Industry

| Indicator | Value/Status | Source(s) |

| Annual Wheat Demand | > 7.0 Million Metric Tons (MMT) | 9 |

| Domestic Wheat Production | Approx. 1.0 – 1.25 MMT | 2 |

| Import Dependency | Approx. 85-90% | 7 |

| Share of Cereal Consumption | Approx. 12% | 2 |

| Per Capita Consumption (Daily) | National Average: 46 g | 2 |

| Urban: 83 g | 2 | |

| Rural: 25 g | 2 | |

| Key Market Drivers | Urbanization, Rising Incomes, Shifting Lifestyles, Health Consciousness, Growth of Food Processing Sector | 1 |

Section 2: The Wheat Supply Conundrum: Domestic Production and Global Dependencies

2.1 Bangladesh’s Wheat Harvest: An Analysis of Domestic Cultivation and Yield Gaps

The foundation of Bangladesh’s flour milling industry is built almost entirely on imported grain, as domestic wheat cultivation is critically insufficient to meet national demand. Domestic production has largely stagnated, stabilizing at an annual output of approximately 1.0 to 1.25 million metric tons (MMT).2 The country’s wheat harvest reached its zenith in the 1999/2000 season, with a production of nearly 2 MMT. However, in the subsequent years, harvested area has declined significantly as farmers have increasingly opted to cultivate other, more profitable crops, particularly Boro rice, which competes for the same land and resources.2

While Bangladesh’s average wheat yield of 2.9 metric tons per hectare is considered high by regional Southeast Asian standards, significant yield gaps remain when compared to global benchmarks.12 The domestic agricultural sector is beset by a number of persistent challenges that constrain its potential. These include the overarching issue of extreme land scarcity, the persistent threat of crop diseases like wheat blast which makes cultivation in many districts a high-risk endeavor, and systemic inefficiencies in the distribution of quality seeds and fertilizers.6 These factors combine to create a situation where a substantial increase in domestic wheat production is highly unlikely in the foreseeable future, cementing the country’s reliance on the global market.

2.2 The Import Imperative: Quantifying the Supply-Demand Deficit

The disparity between domestic supply and national demand is stark and growing. With annual consumption requirements now exceeding 7 to 8 MMT, domestic production covers a mere 14% of the country’s needs.7 This has positioned Bangladesh as one of the world’s top five wheat importers, a status that underscores its vulnerability.6 The supply-demand gap is not static; projections indicate it will continue to widen, potentially surpassing 4 MMT by the year 2030.12

This profound import dependency has significant macroeconomic consequences. It makes the domestic price of a staple food item highly susceptible to fluctuations in international commodity prices, global shipping costs, and the depreciation of the local currency.1 This structural reality means that the inability to boost domestic wheat production is not merely an agricultural concern but a direct contributor to national macroeconomic instability. The constant and massive outflow of foreign currency required for wheat imports—amounting to $823 million in 2023 alone—places immense pressure on Bangladesh’s foreign reserves, which are already under strain.15 Any shock in the global market, whether from conflict, climate events, or trade policy shifts, is immediately transmitted into the domestic economy in the form of food inflation, disproportionately impacting the purchasing power of the most vulnerable households and posing a risk to social stability.

2.3 Global Sourcing Map: A Deep Dive into Key Import Partners and Trade Flows

To meet its vast needs, Bangladesh sources wheat from a diverse but concentrated set of global suppliers. Historically, the Black Sea region, particularly Russia and Ukraine, has been a preferred source due to its cost-competitiveness, supplying up to 40% of the country’s total wheat imports.1 Canada, Australia, and neighboring India have also been significant, long-standing partners.7

The geopolitical shock of the Russia-Ukraine war forced a rapid and necessary diversification of this sourcing map. The conflict severely disrupted shipments from the Black Sea, compelling importers to seek alternatives.1 An analysis of trade flows in 2023 illustrates this new reality: Canada emerged as the single largest supplier, with imports valued at $428 million. Despite the conflict, Ukraine remained a key partner ($171 million), followed by Romania ($105 million), Brazil ($50.7 million), and Australia ($45.1 million).16

A crucial feature of this import landscape is the dominant role of the private sector. Private commercial importers are responsible for sourcing between 75% and 90% of all wheat entering the country.2 This places an immense responsibility on private conglomerates for maintaining the nation’s food supply, while also giving them significant market power and influence.

2.4 Geopolitical and Economic Vulnerabilities in the Wheat Supply Chain

The war between Russia and Ukraine served as a powerful real-world stress test, starkly exposing the profound vulnerabilities inherent in Bangladesh’s food supply chain. The conflict triggered immediate and severe price volatility in global grain markets and created immense uncertainty regarding the availability and shipment of contracted supplies.1 This event catalyzed a strategic re-evaluation within the Government of Bangladesh, leading to a notable pivot in its trade and foreign policy.

In July 2025, facing the dual pressures of a volatile grain market and the looming threat of significant trade tariffs from the United States, the government signed a five-year Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to import 700,000 metric tons of US wheat annually.7 This decision was explicitly and publicly linked to ongoing negotiations aimed at securing relief from a proposed 35% tariff on Bangladeshi exports, particularly ready-made garments, by the Trump administration.7 This strategic maneuver transformed wheat procurement from a purely commercial activity into a tool of international trade diplomacy. The profit margins of the entire flour milling industry, and by extension the price of a staple food for millions, became directly hostage to the outcomes of high-stakes geopolitical negotiations. This situation illustrates that for Bangladeshi millers, risk management must now encompass not only commodity price hedging but also a keen understanding of foreign policy dynamics. The US wheat deal, potentially locking in a higher-cost raw material, was deemed a necessary price to pay to protect the country’s vital, multi-billion-dollar export economy, effectively making the flour industry a strategic pawn in a much larger economic game.

Table 2: Bangladesh Wheat Imports by Source Country (2023)

| Source Country | Import Value (USD Million) | Percentage of Total Imports (%) | Notes |

| Canada | $428 | 52.0% | Became the primary supplier, valued for quality and reliability. |

| Ukraine | $171 | 20.8% | Remained a significant supplier despite ongoing conflict. |

| Romania | $105 | 12.8% | Gained prominence as an alternative Black Sea source. |

| Brazil | $50.7 | 6.2% | An emerging supplier, indicating sourcing diversification. |

| Australia | $45.1 | 5.5% | A traditional partner, maintaining a consistent presence. |

| Others | $23.2 | 2.8% | Includes smaller volumes from various other nations. |

| Total | $823 | 100% | Reflects a shift in sourcing patterns post-2022. |

Source: The Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) 16

Section 3: From Stone to Steel: The Transformation of Bangladesh’s Milling Infrastructure

3.1 The Decline of the ‘Chakki’: A Historical Perspective on Traditional Milling

The origins of Bangladesh’s flour milling industry are rooted in the traditional ‘chakki’ mill. These small-scale operations, typically powered by a diesel engine and utilizing stone grinders often imported from India, have long been a feature of the rural landscape.2 With a modest milling capacity ranging from 300 to 800 kilograms per day, chakki mills have historically served local communities, especially in areas with limited or unreliable access to electricity. They specialize in producing whole-wheat ‘atta’ flour on demand for individual customers, playing a vital role in the local food ecosystem.2 While an estimated 2,000 of these traditional mills are still in operation, their prominence is steadily waning as the industry undergoes a dramatic technological modernization.2

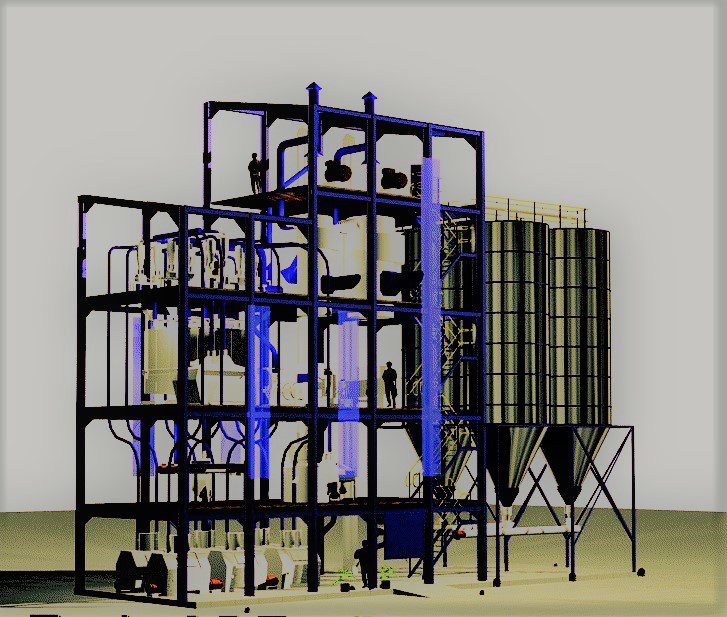

3.2 The Rise of the Roller Mill: Automation, Technology, and Capacity Expansion

The contemporary flour milling industry in Bangladesh is overwhelmingly dominated by modern roller mills, which collectively account for approximately 93% of the country’s total flour production.2 The sector has experienced a remarkable evolution in scale and sophistication. The small-scale roller mills of the 1980s, which had daily capacities of just 10 to 20 metric tons, have been largely superseded by a new generation of industrial facilities capable of milling 300 to 500 tons per day, with the newest and largest plants boasting capacities that are an order of magnitude greater.2

This expansion has been driven by significant capital investment in state-of-the-art European milling technology, signaling a decisive shift towards automation, precision, and efficiency. Leading industry players have partnered with world-renowned equipment suppliers to build their facilities. ACI Pure Flour, for instance, utilizes “Ocrim Machine” technology from Italy in its production lines.20 Similarly, the Swiss engineering group Bühler, a global leader in milling technology, was the turnkey provider for City Group’s colossal Rupshi Flour Mill and Akij Resource’s new facility.21 This adoption of cutting-edge technology reflects a strategic imperative to enhance product quality, increase extraction rates, and achieve the economies of scale necessary to compete in a rapidly modernizing market.

3.3 A Segmented Industry: Profiling Micro, Small, Medium, and Large-Scale Mills

Despite the rise of industrial giants, the structure of the Bangladeshi milling sector remains highly segmented and dualistic. The industry can be broadly categorized into three tiers:

- Large-Scale Mills: Approximately 20 large, highly capitalized plants form the apex of the industry. These facilities typically have a milling capacity ranging from 100 to over 500 metric tons per day.4

- Small and Medium-Sized Mills: This segment comprises an estimated 300 to 350 mills with daily capacities falling between 10 and 100 metric tons.4

- Traditional ‘Chakki’ Mills: At the base of the pyramid are the approximately 2,000 traditional stone mills, each with a capacity of less than one metric ton per day.4

This structure reveals an industry where a small number of technologically advanced players control the vast majority of the market’s volume and value, coexisting with a large number of small, traditional operators who cater to localized, niche demand. This dynamic is creating what can be described as a “technology moat.” The massive capital expenditure required to build and operate a modern mill creates formidable barriers to entry. The superior efficiency, quality control, and scale of these new plants allow the large conglomerates to produce flour at a lower per-unit cost, enabling them to compete aggressively on price. Simultaneously, their advanced systems allow them to meet the stringent quality specifications of industrial buyers and build the brand trust necessary to command a premium in the retail market. This creates a powerful feedback loop where the largest players are best positioned to grow, which will likely accelerate market consolidation over the medium term as smaller, less efficient mills find it increasingly difficult to compete.

3.4 Investment in Innovation: Case Studies in Modern Milling Technology

The scale of recent investments provides a clear window into the industry’s future trajectory. Two projects in particular stand out as exemplars of this transformation:

City Group’s Rupshi Flour Mill: This facility is a testament to the scale and ambition of the industry’s leaders. As City Group’s largest mill and one of the biggest in the world, it has a staggering total production capacity of 6,150 metric tons per day, achieved through eight parallel milling lines, each supplied by Bühler.21 The integrated facility is not just a mill but a complete logistics hub, featuring 39 storage silos with a combined capacity of 305,000 tons. This massive storage capability is enhanced with modern technology, including Bühler’s “Insights” solution, which allows for real-time monitoring of temperature and conditions within each silo.21 This level of investment in storage is a crucial strategic asset, allowing the company to mitigate the risks of supply chain volatility. By enabling the purchase of vast quantities of wheat when global prices are favorable, such facilities insulate the company from short-term price spikes and shipping delays, ensuring operational continuity and providing a significant commercial advantage over smaller competitors.

Meghna Group of Industries’ (MGI) Green Mill: A $20 million loan agreement with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) is financing the construction of a new, energy-efficient flour mill for MGI.14 This project signals a new direction for the industry, with a strong focus on sustainability. The plant is designed to consume 37% less electricity than conventional mills, which is projected to reduce annual carbon dioxide emissions by approximately 8,200 tonnes.14 This focus on “green” technology is a shrewd business strategy. In a country where operational challenges include frequent power shortages, reducing energy consumption directly lowers long-term operational costs, enhancing profitability and resilience. Furthermore, adhering to stringent environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards is often a prerequisite for securing favorable financing from development institutions like the ADB, turning sustainability into a key enabler of growth.

Section 4: Competitive Landscape and Key Market Players

4.1 Market Structure and Brand Dominance: Teer, Fresh, ACI, and Emerging Players

The consumer-facing flour market in Bangladesh exhibits the classic characteristics of an oligopoly, where a small number of large, well-established firms command a dominant share of the market. A landmark 2013 consumer survey provided a clear snapshot of this structure, identifying the top three brands by market share as:

- Teer (City Group): 44%

- Fresh (Meghna Group of Industries): 22%

- ACI Pure (ACI Limited): 18% 3

These three brands collectively controlled 84% of the market at the time of the survey, with all other players holding shares of less than 5% each. While the market has evolved, the fundamental dominance of these large players remains. A subsequent study confirmed the continued market leadership of the Teer brand in the critical Dhaka market. However, it also highlighted the existence of strong regional players, with the “Pusti” brand showing dominance in Chittagong’s Atta and Maida segments, and the “Horse” brand leading in the Suji category in the same city.25 In recent years, the

Bashundhara Group has also made significant inroads, establishing its brand as a top contender in the market.27 This competitive environment is dynamic, but the high barriers to entry in terms of capital investment for modern milling and logistics mean that the market is likely to remain concentrated among these major conglomerates.

4.2 Profiles of Industry Leaders

The flour milling industry is a strategic battleground for some of Bangladesh’s largest and most diversified business conglomerates. For these groups, the flour division often serves as a stable, high-volume “cash cow,” generating consistent cash flow that can be reinvested into other, often higher-growth or higher-risk, ventures across their portfolios, from real estate and media to banking and energy.

- 4.2.1 City Group: Founded in 1972, City Group is a titan of the Bangladeshi food industry. Its flagship flour brand, TEER, is the undisputed market leader.3 The group’s market power is anchored by its immense production scale, epitomized by the Rupshi Flour Mill. With a daily capacity of 6,150 metric tons, it is the largest mill in South Asia and provides City Group with unparalleled economies of scale.21

- 4.2.2 ACI Pure Flour Ltd.: A subsidiary of the diversified conglomerate ACI Limited, ACI Pure Flour was established in 2008 and has since carved out a position as the industry’s innovation leader.20 The company has been a first-mover in several key areas, introducing the country’s first laminated packaging for flour to improve shelf life and hygiene, and pioneering value-added products like “ACI Pure Brown Atta” and “Nutrilife Multigrain Atta”.20 It operates a 300 MT/day factory in Narayanganj and leases an additional 450 MT/day facility in Chittagong, giving it a total stated capacity of 750 MT/day.20

- 4.2.3 Meghna Group of Industries (MGI): MGI is another of the country’s leading conglomerates, and its Fresh brand is a powerhouse in the FMCG sector. “Fresh Atta-Maida-Suji” holds the number two position in the market and has been consistently recognized for its quality, winning the “Best Brand Award” for six consecutive years.29 MGI is actively expanding its capacity with the construction of a new, energy-efficient mill.14

- 4.2.4 Bashundhara Group (BFBIL): Bashundhara Food and Beverage Industries Limited (BFBIL) represents the formidable entry of another major conglomerate into the sector. The group has rapidly established its Bashundhara brand as a top-tier player, supported by a recently completed integrated flour mill facility with a combined capacity of 1,200 MT/day.2

- 4.2.5 Other Notable Millers: Beyond the top tier, several other significant players contribute to the market. These include Nabil Auto Flour Mills, part of the Nabil Group, with a large facility in Rajshahi boasting a 1,000 MT/day capacity 31;

Hashem Flour Mills Ltd., a sister concern of the Sajeeb Group 32; and

Star Line Major Flour Mills, part of the Star Line Group.33

4.3 Product Portfolio Analysis: Atta, Maida, Suji, and Value-Added Innovations

The product portfolio of Bangladeshi flour mills is centered around three core offerings tailored to traditional culinary uses:

- Atta: A whole or semi-hard whole wheat flour, which is the staple for making flatbreads like ‘roti’ and ‘chapati’.2

- Maida: A finer, refined all-purpose white flour produced from the endosperm of the wheat grain. It is the primary ingredient for bakery products like bread and pastries, as well as traditional snacks.2

- Suji: Also known as semolina, this is a coarse flour made from durum wheat, commonly used for making porridges, desserts, and pasta.31

While these three products form the bedrock of the market, the key competitive frontier is increasingly shifting towards value-added and differentiated products. This trend is a direct response to the demands of the growing urban middle class, which is more health-conscious and willing to pay a premium for specialized goods. ACI has been particularly adept at capitalizing on this shift. The company has successfully marketed its “ACI Pure Brown Atta” as a healthier alternative, even promoting it directly to doctors and health practitioners to build credibility.20 Its portfolio also includes innovative products like “ACI Nutrilife Multigrain Atta” and a convenient “Instant Suji Mix”.20 City Group has also entered this space with its “TEER Whole Wheat Atta”.28 In a market where the core products are largely undifferentiated, these innovations, along with third-party endorsements like the “Best Brand Award” won by Fresh, become crucial competitive tools. They allow companies to build brand equity, command higher price points, and capture the most profitable segments of the consumer market, effectively turning a basic commodity into a trusted consumer brand.

Table 3: Comparative Profile of Major Flour Milling Companies in Bangladesh

| Company/Group | Flagship Brand(s) | Stated Production Capacity (MT/day) | Key Technology/Infrastructure | Notable Market Position/Strategy | Source(s) |

| City Group | TEER | 6,150 | Bühler milling lines, 305,000 MT silo storage with monitoring tech | Undisputed market share leader; focus on massive scale and efficiency. | 21 |

| ACI Pure Flour Ltd. | ACI Pure | 750 (300 owned + 450 leased) | European “Ocrim Machine” technology | Innovation leader; pioneer in value-added products (Brown/Multigrain Atta) and packaging. | 20 |

| Meghna Group (MGI) | Fresh | Not specified | Building new energy-efficient mill with ADB financing | Strong No. 2 market position; consistent winner of “Best Brand” awards, leveraging strong brand equity. | 14 |

| Bashundhara Group (BFBIL) | Bashundhara | 1,200 | Integrated flour mill facility | Major conglomerate that has rapidly become a top-tier brand in the market. | 2 |

| Nabil Group | Nabil | 1,000 | Two advanced production units in Rajshahi | Significant player with large-scale capacity, focusing on North Bengal region. | 31 |

Section 5: Economic Significance and Value Chain Contribution

5.1 A Pillar of Food Security: The Industry’s Role in National Sustenance

The flour milling industry serves as an indispensable pillar of Bangladesh’s national food security framework. With wheat established as the second most vital staple food after rice, the industry’s capacity to efficiently and affordably process raw grain into flour is essential for the sustenance of the nation’s more than 170 million people.1 The government and international development partners explicitly recognize this role. Large-scale investments in the sector, such as the new energy-efficient mill being constructed by Meghna Group of Industries (MGI) with support from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), are framed not just as commercial ventures but as strategic projects aimed at enhancing national food security by bolstering domestic processing capacity and reducing the risks associated with import dependency.14

5.2 Contribution to the Agro-Processing Sector and National GDP

The agro-food processing sector, of which flour milling is a major sub-component, makes a significant contribution to the national economy. This sector accounts for approximately 1.7% of Bangladesh’s total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and represents about 8% of the total manufacturing output.36 While specific, disaggregated data on the direct GDP contribution of flour milling alone is not readily available, its importance is tracked by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) through its Quantum Index of Industrial Production (QIIP) for Flour Milling. This index serves as a reliable proxy for measuring the sector’s output growth and its contribution to the broader industrial economy over time.38 The milling industry operates within the context of the wider agriculture sector, which, despite a declining share of the overall economy, remains a vital contributor, accounting for between 12.5% and 14.5% of the national GDP.36

The true economic impact of the flour milling industry, however, extends far beyond its direct share of GDP. It functions as a crucial economic multiplier and an enabling platform for a host of other significant industries. The availability of a consistent and affordable supply of high-quality flour is a fundamental prerequisite for the entire urban food service economy, which includes thousands of bakeries, restaurants, and fast-food outlets, and is a major source of urban employment. Similarly, the country’s growing, multi-million-dollar export industry for finished wheat-based products is entirely dependent on the domestic milling sector for its primary raw material. Consequently, any disruption or inefficiency within the flour milling value chain would have immediate and cascading negative effects on these larger downstream sectors, demonstrating that the industry’s systemic importance to the national economy is far greater than its direct statistical contribution suggests.

5.3 Employment Generation: From Farm to Factory to Fork

The agro-food processing industry is a significant source of employment in Bangladesh, providing livelihoods for approximately 250,000 people, which corresponds to about 2.2% to 2.45% of the country’s total labor force.36 While comprehensive employment statistics for the flour milling sector specifically are not published, data from online job portals indicates active and ongoing recruitment for a range of positions, from technical roles like Machine Operators to managerial positions such as Production Supervisors and Supply Chain Management officers at major mills including Hashem Flour Mill and Akij Flour Mills.43

New investments in the sector are a direct catalyst for job creation. The new MGI mill, for example, is projected to create 160 direct jobs upon completion. Its economic impact extends further down the value chain, as the project is expected to foster and support a network of 150,000 vendors in the Small and Medium-sized Enterprise (SME) sector, including suppliers, distributors, and retailers.14 As the industry continues its technological transformation from traditional, labor-intensive methods to modern, automated processes, the nature of employment is also shifting. The demand is moving away from unskilled labor towards a more technically proficient workforce, including engineers, IT specialists, and skilled machine operators capable of managing sophisticated, computer-controlled milling systems. This evolution points to a potential future skills gap and highlights the need for vocational and technical training programs aligned with the industry’s changing requirements.

5.4 Beyond Borders: The Growing Export Market for Bangladeshi Wheat-Based Products

The flour milling industry is increasingly serving as a foundation for Bangladesh’s ambitions to move up the global food value chain. Beyond satisfying domestic consumption, the sector is a critical supplier to a burgeoning export market for processed, wheat-based foods. In the fiscal year 2023-24, the total export value of these products—which include items such as bread, pastries, cakes, biscuits, and pasta—was estimated at $217.7 million. This figure is projected to grow further, reaching $225 million in fiscal year 2024-25.8

The primary destinations for these exports include countries with large Bangladeshi diaspora populations, such as Saudi Arabia, Oman, Malaysia, the United States, and the United Kingdom.8 This growing export trade is strategically important, as it demonstrates the country’s capacity to transform an imported raw commodity (wheat) into value-added, finished goods for the international market, thereby capturing a greater share of the economic value and generating valuable foreign exchange earnings.

Section 6: Navigating the Regulatory and Policy Framework

6.1 Government Procurement and Public Food Distribution System (PFDS)

The Government of Bangladesh (GoB) is an active participant in the grain market, primarily through its Public Food Distribution System (PFDS). This system is a key component of the country’s social safety net, designed to ensure food availability for vulnerable populations through various subsidized distribution programs.46 To support the PFDS, the government maintains a public food stock, procuring wheat and other grains from both international and domestic sources. However, given the minimal domestic wheat harvest, government procurement is overwhelmingly reliant on international tenders.6 For the fiscal year 2023-24, the government set a target to distribute 0.67 million metric tons (MMT) of wheat through the PFDS, highlighting its significant role as a market player.11

6.2 Trade Policy: An Analysis of Import Tariffs and Strategic Agreements

Trade policy, particularly the structure of import tariffs, is a primary lever used by the government to influence the domestic flour market. The National Board of Revenue (NBR) administers a complex tariff schedule for wheat, which includes multiple layers of taxation such as Customs Duty (CD), Supplementary Duty (SD), Value Added Tax (VAT), Advance Income Tax (AIT), Advance Tax (AT), and Regulatory Duty (RD), with specific rates varying based on the Harmonized System (HS) Code of the product (e.g., durum vs. other wheat, seed vs. grain, packaged vs. bulk).47

The government has historically used adjustments to this tariff structure as a tool for market stabilization. In periods of high domestic food inflation, authorities have often lowered or temporarily waived certain duties to encourage private sector imports and alleviate price pressure on consumers.9 A notable example occurred in December 2020, when the NBR removed the 5% Advance Income Tax (AIT) on all wheat imports to streamline the process and reduce the landed cost of the grain.52 While these interventions can provide short-term relief, their often ad-hoc nature creates an unpredictable operating environment for private millers, complicating long-term procurement planning and investment decisions. A sudden tariff reduction can significantly erode the margins of a miller who has already committed to a shipment based on the previous cost structure.

In recent years, trade policy has also been wielded as an instrument of broader geopolitical strategy. The 2025 MoU to import 700,000 MT of wheat annually from the United States is a clear instance of this. The agreement was explicitly framed as part of an effort to strengthen bilateral relations and negotiate potential relief from punitive tariffs threatened by the US on Bangladesh’s crucial ready-made garment exports.53 This intertwining of food procurement with high-stakes trade diplomacy adds another layer of complexity and risk for the industry.

Table 4: Bangladesh Customs Tariff Schedule for Wheat (HS Code 1001), FY 2025-26

| HS Code | Description | CD (%) | SD (%) | VAT (%) | AIT (%) | AT (%) | RD (%) | TTI (%) |

| 10011110 | Durum wheat Seed, Wrapped/canned up to 2.5 Kg | 5.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 10.00 |

| 10011190 | Durum wheat Seed, EXCL. Wrapped/canned up to 2.5 Kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 10011910 | Durum wheat, Other than Seed, Wrapped/canned up to 2.5 Kg | 5.00 | 0.00 | 15.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 26.50 |

| 10011990 | Durum wheat, Other than Seed, EXCL. Wrapped/canned up to 2.5 Kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 10019990 | Other Wheat and Meslin, Other than Seed, EXCL. Wrapped/canned up to 2.5 Kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Source: Bangladesh Customs 47; National Board of Revenue.47 Note: TTI (Total Tax Incidence) is an aggregate measure and may vary. This table presents a selection of key HS codes for wheat; the full tariff schedule contains additional codes.

6.3 Ensuring Quality and Safety: The Role of BSTI and the Food Safety Act

The quality and safety of flour and other food products are governed by a dual regulatory framework. The Bangladesh Standards and Testing Institution (BSTI) serves as the national standards body, responsible for formulating and enforcing specific quality standards for a wide range of products. For the flour industry, there are several mandatory standards, including:

- BDS 380 for Wheat Atta

- BDS 381 for Maida (Wheat Flour)

- BDS 190 for Suji (Semolina) 57

These standards prescribe detailed requirements for parameters such as moisture content, total ash, acid-insoluble ash, gluten content, and granularity, and also set rules for packaging and labeling.58 The use of the BSTI Certification Mark on product packaging, which signals compliance with these standards, is governed by the BSTI Act of 2018.59

The broader legal architecture for food safety is established by the Food Safety Act of 2013. This landmark legislation created the Bangladesh Food Safety Authority (BFSA) as the central coordinating body with a mandate to regulate all activities related to the production, import, processing, storage, and sale of food.61 The BFSA’s role is to ensure access to safe food through the application of scientific methods and to harmonize the efforts of various government agencies. However, some reports suggest that the existence of numerous laws and the overlapping jurisdictions of different bodies can lead to complexity and challenges in consistent enforcement across the entire industry, particularly among the vast number of smaller, less-formal operators.62

Section 7: Strategic Analysis: Challenges, Opportunities, and Future Trajectory

7.1 Prevailing Headwinds: Supply Chain Risks, Price Volatility, and Operational Hurdles

The flour milling industry in Bangladesh, despite its strong demand fundamentals, operates in an environment fraught with significant challenges and risks. The most profound of these is the sector’s extreme dependence on imports. This structural vulnerability exposes the entire value chain to the vagaries of the global market, including commodity price shocks, geopolitical conflicts that can disrupt key supply routes like the Black Sea, and escalating international shipping costs.1

These external risks are compounded by a challenging domestic macroeconomic environment. Persistently high inflation erodes the purchasing power of consumers, limiting their ability to absorb price increases. Simultaneously, the depreciation of the Bangladeshi Taka and the depletion of the country’s foreign exchange reserves directly increase the cost of importing wheat, which is traded in US dollars, thereby creating a severe margin squeeze for millers.1 On an operational level, millers also contend with domestic hurdles such as unreliable power supplies, which can halt production and increase costs, limited access to affordable financing, and an underdeveloped and inefficient national transportation infrastructure that complicates logistics and distribution.1

7.2 Avenues for Growth: Branded Products, Health & Wellness, and Export Markets

Despite the headwinds, the industry is presented with multiple, clearly defined avenues for future growth. The most significant opportunity lies in continuing the transition from a commodity-driven market to a brand-centric one. The ongoing shift in consumer preference from loose, unbranded flour to hygienic, quality-assured packaged products creates immense potential for brand building and value creation.3

Within this trend, the health and wellness segment is particularly promising. As urban consumers become more health-conscious, there is a growing market for differentiated, value-added products such as brown atta, multigrain atta, and fortified flours.3 Companies that can successfully innovate and market these products can capture higher margins and build strong brand loyalty. Another key growth vector is the export market. The increasing demand for Bangladeshi processed foods in international markets, particularly among diaspora communities, provides a high-growth outlet for domestically milled flour, allowing the industry to participate in the global value chain.8 Finally, the substantial disparity in per capita flour consumption between urban and rural areas highlights the vast, largely untapped potential of the rural market, which represents the next frontier for long-term expansion.4

7.3 The Sustainability Imperative: Energy Efficiency and Environmental Responsibility

Sustainability is emerging as a key strategic consideration for the industry’s future. This is driven not only by a sense of corporate responsibility but also by compelling economic and financial incentives. New investments in the sector are increasingly prioritizing the adoption of energy-efficient technologies. As demonstrated by MGI’s new ADB-funded mill, these technologies can dramatically reduce operational costs in an energy-scarce environment, directly enhancing long-term profitability and competitiveness.14

A commitment to sustainable practices—encompassing economic viability, social responsibility through fair labor practices and community engagement, and environmental stewardship by minimizing the ecological footprint and reducing waste—is becoming a critical factor for securing financing from international development institutions and meeting the evolving expectations of both domestic consumers and international buyers.34

7.4 Future Outlook: Projections for Demand, Investment, and Technological Adoption

The outlook for the Bangladeshi flour milling industry is one of continued growth, driven by enduring demographic and economic trends. Demand for wheat is forecast to maintain its strong upward trajectory, with total import requirements projected to reach 6.9 MMT in the 2025/26 marketing year.8 Projections from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations confirm that Bangladesh will remain heavily reliant on imports to meet its consumption needs, forecasting an import requirement of 6.7 MMT for the 2024/25 period.64

To meet this escalating demand, continued investment in the sector is anticipated. This investment will likely be concentrated in the development of large-scale, highly automated, and energy-efficient milling facilities, as companies seek to enhance productivity, improve quality, and lower their cost base to remain competitive.23 The technological modernization of the industry is expected to accelerate, further widening the gap between the technologically advanced industry leaders and smaller, traditional mills.

Section 8: Strategic Recommendations for Stakeholders

8.1 For Industry Players: Strategies for Enhancing Competitiveness and Resilience

- Diversify Sourcing and Invest in Sophisticated Risk Management: To mitigate the extreme volatility of the global grain market, millers must move beyond opportunistic procurement and develop a formal, diversified global sourcing strategy that reduces over-reliance on any single geographic region. This should be complemented by investing in in-house or third-party expertise in commodity hedging and other financial risk management tools to protect margins from price and currency fluctuations.

- Accelerate the Shift from Commodity to Brand: The future of the retail market lies in brand equity. Companies should double down on investments in marketing and brand building to foster consumer trust and loyalty. This must be supported by a robust R&D pipeline focused on developing innovative, value-added products that cater to the growing health, wellness, and convenience segments, allowing firms to move up the value chain and away from pure price competition.

- ** relentlessly Pursue Operational Excellence:** Continue to invest in energy-efficient and automated technologies to drive down operational costs, which is a key competitive advantage in a high-volume, low-margin business. Focus on strengthening supply chain and distribution logistics to ensure product availability across all regions, as this is a primary driver of consumer choice.

8.2 For Investors: Identifying High-Potential Investment Areas in the Value Chain

- Modern Milling and Storage Capacity: Given the unabated growth in demand, there remain attractive opportunities for greenfield investments in large-scale, technologically advanced, and energy-efficient milling facilities. Co-locating these mills with significant modern grain storage capacity (silos) offers an integrated model that can mitigate supply risk and capture trading opportunities.

- Downstream Value-Added Processing: Significant potential exists in investing in downstream food processing businesses that can leverage the growing supply of high-quality domestic flour. This includes ventures in premium and artisanal bakeries, industrial-scale manufacturing of noodles and pasta, and the fast-growing frozen and ready-to-eat foods segment.

- Enabling Infrastructure and Services: The industry’s bottlenecks represent investment opportunities. Ventures focused on modernizing grain logistics, providing third-party temperature-controlled warehousing and transportation, and developing digital platforms for supply chain management can address critical pain points and generate strong returns.

8.3 For Policymakers: Recommendations for Fostering Sustainable Growth and Food Security

- Develop a Long-Term Domestic Agriculture Strategy: While self-sufficiency is unrealistic, a concerted, long-term national strategy to improve domestic wheat yields is a matter of economic security. This should involve funding research into climate-resilient and saline-tolerant wheat varieties, reforming the seed and fertilizer distribution systems to ensure quality and access for farmers, and strengthening agricultural extension services.

- Ensure a Stable and Transparent Trade Policy Environment: While tactical tariff adjustments may be necessary, the government should strive to create a more stable and predictable trade policy framework to allow businesses to engage in long-term planning and investment. Trade diplomacy should focus on securing reliable and cost-effective wheat supplies from a diverse portfolio of countries, avoiding over-dependence on any single partner.

- Prioritize Investment in Enabling Infrastructure and Skills Development: Public investment in reliable power generation and upgrading national transportation networks (roads, railways, and ports) is critical to reducing operational costs and improving efficiency for the entire industry. Furthermore, the government should partner with industry associations and educational institutions to develop vocational training programs that create a pipeline of skilled technicians and engineers required to operate and maintain the modern, automated mills of the future.

Works cited

- Flour Milling Industry in Bangladesh: Flourishing through Automation – IDLC, accessed July 22, 2025, https://idlc.com/mbr/images/public/jFBEGq36INCoqgXnS9UuAX.pdf

- Wheat Milling in Bangladesh, accessed July 22, 2025, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=Wheat%20Milling%20in%20Bangladesh_Dhaka_Bangladesh_3-22-2013.pdf

- Market insight flour industry in bangladesh | PDF – SlideShare, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/market-insight-flour-industry-in-bangladesh/45875922

- Grain and Flour Market in Bangladesh (Yazılar EN) – Miller Magazine, accessed July 22, 2025, https://millermagazine.com/articles/grain-and-flour-market-in-bangladesh-yazlar-en-8

- Grain and Flour Market in Bangladesh (Yazılar TR) – Miller Magazine, accessed July 22, 2025, https://millermagazine.com/tr/articles/grain-and-flour-market-in-bangladesh-18

- Bangladesh Wheat Sector: Battling Demand-Supply Mismatch – LightCastle Partners, accessed July 22, 2025, https://lightcastlepartners.com/insights/2019/10/bangladesh-wheat-sector-demand-supply-mismatch/

- Bangladesh commits to import more US wheat – World Grain, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.world-grain.com/articles/21648-bangladesh-commits-to-import-more-us-wheat

- Wheat demand surges amid dietary shifts, flourishing industries, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.daily-sun.com/printversion/details/800024

- Bangladesh to double wheat imports amid global supply challenges – The Daily Ittefaq, accessed July 22, 2025, https://en.ittefaq.com.bd/12731/bangladesh-to-double-wheat-imports-amid-global

- Flour prices on rise in Bangladesh | The Financial Express, accessed July 22, 2025, https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/home/flour-prices-on-rise-in-bangladesh-1650341707

- BaNGLADESH FOOD SITUATION REPORT Overview, accessed July 22, 2025, https://fpmu.mofood.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/fpmu.mofood.gov.bd/miscellaneous_info/8bac2269_baf2_4c66_be41_ca0447d878ef/2024-05-07-04-58-85e0a249e464799d4a280467f40892cb.pdf

- Wheat Value Chain: Bangladesh | EPAR – University of Washington, accessed July 22, 2025, https://epar.evans.uw.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/EPAR_UW_203_Wheat_Bangladesh_07312012.pdf

- (PDF) Challenges and Opportunities of Bangladesh Agriculture Sector: The Role of Chemical Fertilizer and Scope of Organic Farming – ResearchGate, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/386248321_Challenges_and_Opportunities_of_Bangladesh_Agriculture_Sector_The_Role_of_Chemical_Fertilizer_and_Scope_of_Organic_Farming

- ADB, Meghna Group ink $20m deal for green flour mill project | The …, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.tbsnews.net/economy/corporates/adb-meghna-group-partner-food-security-and-energy-boost-1010626

- Report Name: Grain and Feed Annual – USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, accessed July 22, 2025, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Grain%20and%20Feed%20Annual_Dhaka_Bangladesh_BG2024-0002.pdf

- Wheat in Bangladesh Trade | The Observatory of Economic …, accessed July 22, 2025, https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-product/wheat/reporter/bgd

- Bangladesh to import 700 thsd tons of wheat from the US annually, accessed July 22, 2025, https://ukragroconsult.com/en/news/bangladesh-to-import-700-thsd-tons-of-wheat-from-the-us-annually/

- Bangladesh Government Commits to Annual Purchases of 700,000 Metric Tons of U.S. Wheat | American Ag Network, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.americanagnetwork.com/2025/07/21/bangladesh-government-commits-to-annual-purchases-of-700000-metric-tons-of-u-s-wheat/

- BD signs US wheat-import deal in bid to curb tariff pressure – World – Business Recorder, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.brecorder.com/news/amp/40373592

- ACI Pure Flour Ltd. – ACI PLC – ACI Limited, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.aci-bd.com/our-companies/aci-pure-flour-ltd.html

- Bühler hands over Rupshi Flour Mill in Bangladesh to City Group in …, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.buhlergroup.com/global/en/media/media-releases/buehler_hands_overrupshiflourmillinbangladeshtocitygroupinrecord.html

- New flour mill opens in Bangladesh | World Grain, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.world-grain.com/articles/20243-new-flour-mill-opens-in-bangladesh

- ADB and MGI sign deal to construct flour mill in Bangladesh, accessed July 22, 2025, https://millingandgrain.com/adb-and-mgi-sign-deal-to-construct-flour-mill-in-bangladesh/

- MGI to build flour mill in Bangladesh – World Grain, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.world-grain.com/articles/20777-mgi-to-build-flour-mill-in-bangladesh

- Wheat Flour Marketing in Bangladesh: a case study on packaged Atta, Maida and Semolina in two major City Corporations of Bangladesh, accessed July 22, 2025, https://catalog.ihsn.org/citations/42762

- Wheat Flour Marketing in Bangladesh: a case study on packaged Atta, Maida and Semolina in two major City Corporations of Bangladesh | Mahmud | European Journal of Business and Management, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/EJBM/article/view/9455

- Bashundhara Food top brand in wheat products market – Daily Sun, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.daily-sun.com/post/509994

- History – City Group, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.citygroup.com.bd/history

- Fresh Atta-Maida-Suji gets ‘Best Brand’ award – The Financial Express, accessed July 22, 2025, https://today.thefinancialexpress.com.bd/trade-market/fresh-atta-maida-suji-gets-best-brand-award-1641745563

- Fresh Atta-Maida-Suji, Refined Sugar again recognized as ‘best brand’ – Dhaka Tribune, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.dhakatribune.com/business/261471/fresh-atta-maida-suji-refined-sugar-again

- Nabil Auto Flour Mills – NGI, accessed July 22, 2025, https://ngibd.com/food-and-beverages/nabil-auto-flour-mills/

- Hashem Flour Mills Ltd – Sajeeb Group, accessed July 22, 2025, https://sajeebgroup.com.bd/hashem-flour-mills-ltd/

- Star Line Major Flour Mills – Star Line Group, accessed July 22, 2025, https://starlinegroupbd.com/star-line-major-flour-mills/

- (PDF) SUSTAINABLE GROWTH AND FINANCIAL VIABILITY OF FLOUR MILL INDUSTRIES IN BANGLADESH: A CASE STUDY – ResearchGate, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373444483_SUSTAINABLE_GROWTH_AND_FINANCIAL_VIABILITY_OF_FLOUR_MILL_INDUSTRIES_IN_BANGLADESH_A_CASE_STUDY

- MGI’s concern, ADB sign $20 million loan deal for flour milling plant | The Daily Star, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.thedailystar.net/business/news/mgis-concern-adb-sign-20-million-loan-deal-flour-milling-plant-3769076

- Agro Processing – BIDA, accessed July 22, 2025, https://bida.gov.bd/agro-processing

- Agro-food processing industry in Bangladesh: An overview | The Financial Express, accessed July 22, 2025, https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/agro-food-processing-industry-in-bangladesh-an-overview-1572707863

- Bangladesh GDP: Industry: Mfg: Cottage Industry | Economic Indicators – CEIC, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/bangladesh/sna08-gdp-by-industry-current-price-annual/gdp-industry-mfg-cottage-industry

- Bangladesh Quantum Index: FB: Flour Milling | Economic Indicators – CEIC, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/bangladesh/industrial-production-quantum-index-198889100-medium-and-large-scale-manufacturer/quantum-index-fb-flour-milling

- Bangladesh – Agriculture Sectors – International Trade Administration, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/bangladesh-agriculture-sectors

- Economy of Bangladesh – Wikipedia, accessed July 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_Bangladesh

- Food and Beverage Industry in Bangladesh | Project Profile, accessed July 22, 2025, https://projectsprofile.com/info/potential_five.html

- Flour Mill jobs in Bangladesh – July 2025 – Jora, accessed July 22, 2025, https://bd.jora.com/Flour-Mill-jobs-in-Bangladesh

- Flour Jobs in Dhaka | Careerjet, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.careerjet.com.bd/flour-jobs/Dhaka

- Mill Jobs in Bangladesh – Dhaka – Careerjet, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.careerjet.com.bd/mill-jobs.html

- Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Ministry of Food Modern Food Storage Facilities Project (MFSP) Terms of Refe, accessed July 22, 2025, https://dgfood.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/dgfood.portal.gov.bd/page/cb9f6c96_eeef_486e_adb9_c7b3e786f761/Final%20TOR%20for%20Integrated%20Research%20Program-08-06-01-15.pdf

- Customs Tariff Fiscal Year: 2025-2026 HSCODE …, accessed July 22, 2025, https://customs.gov.bd/files/Tariff-2025-2026(02-06-2025).pdf

- (Value in taka) HS Code value value value IMPORT TOTAL 4762386696873 4432960866411 9195347563284 01 LIVE ANIMALS 2200722264 1955, accessed July 22, 2025, https://bbs.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bbs.portal.gov.bd/page/8643ec8b_27a3_41cd_bbd9_9be3479f578e/2024-05-12-07-37-bee60d7ae6906208467b161eb28f7434.pdf

- Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Nation Board of Revenue National Customs Tariff, FY:2024-2025 HSCODE DESCRIPTION CD SD VAT AIT RD AT – NBR, accessed July 22, 2025, https://nbr.gov.bd/uploads/budget_at_a_glance/TRF2425(TTI)06-06-2024.pdf

- Chapter 11 – NBR, accessed July 22, 2025, https://nbr.gov.bd/uploads/tariff_schedule/Chapter-11.pdf

- Bangladesh to import 7 lakh MTs of wheat from US, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.observerbd.com/news/535224

- NBR removes tax on wheat imports – The Daily Star, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.thedailystar.net/business/news/nbr-removes-tax-wheat-imports-2011585

- Govt to import wheat from US, MoU signing today – Prothom Alo English, accessed July 22, 2025, https://en.prothomalo.com/business/local/umo3di1nf2

- Bangladesh considers tariff cuts on US imports | Prothom Alo, accessed July 22, 2025, https://en.prothomalo.com/business/epn36zjwlz

- US tariff: Dhaka open to trade concessions but set to reject non-trade conditions, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.tbsnews.net/economy/us-tariff-dhaka-open-trade-concessions-set-reject-non-trade-conditions-1192881

- 700,000 tonnes of wheat import deal with US amid rising tariffs | The Financial Express, accessed July 22, 2025, https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/trade/700000-tonnes-of-wheat-import-deal-with-us-amid-rising-tariffs

- BSTI Product List | PDF | Ac Power Plugs And Sockets | Insulator …, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/509241539/BSTI-product-list

- BSTI STANDARDS CATALOGUE 2021(Till August 2021), accessed July 22, 2025, https://bsti.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bsti.portal.gov.bd/page/c82bd863_c051_46ce_af11_eb5bec479d5b/2021-08-31-11-36-54b7b1099157fbe275580fb4511a00bf.pdf

- Draft for public comments only, not to be cited as BDS, accessed July 22, 2025, https://bsti.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bsti.portal.gov.bd/notices/5df65343_98d6_47b0_a69e_d64d4543759b/2022-12-11-05-17-d9c6a148e943deb6f55cebb6302a412e.pdf

- Bangladesh Standard Specification For Wafer Biscuits, accessed July 22, 2025, https://sps.gdtbt.org.cn/upload/ueditor/upload/file/20250516/6388300793841768884646774.pdf

- Bangladesh Food Safety Authority Ministry of Food, Govt. of Bangladesh Dhaka, accessed July 22, 2025, https://bangladeshbiosafety.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/BFSA-Strategy-for-Harmoniztion-of-Standards-draft-V-1.pdf

- Bangladesh Food and Agricultural Import Regulations and Standards Report FAIRS Annual Country Report, accessed July 22, 2025, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=Food%20and%20Agricultural%20Import%20Regulations%20and%20Standards%20Report_Dhaka_Bangladesh_4-15-2019.pdf

- Report Name: Grain and Feed Annual – USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, accessed July 22, 2025, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Grain%20and%20Feed%20Annual_Dhaka_Bangladesh_BG2025-0004.pdf

- FAO GIEWS Country Brief on Bangladesh -, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.fao.org/giews/countrybrief/country.jsp?code=BGD